Research

Effects of incorrectly modeling diffuse radiance (either from terrain or background) on snow reflectance spectra

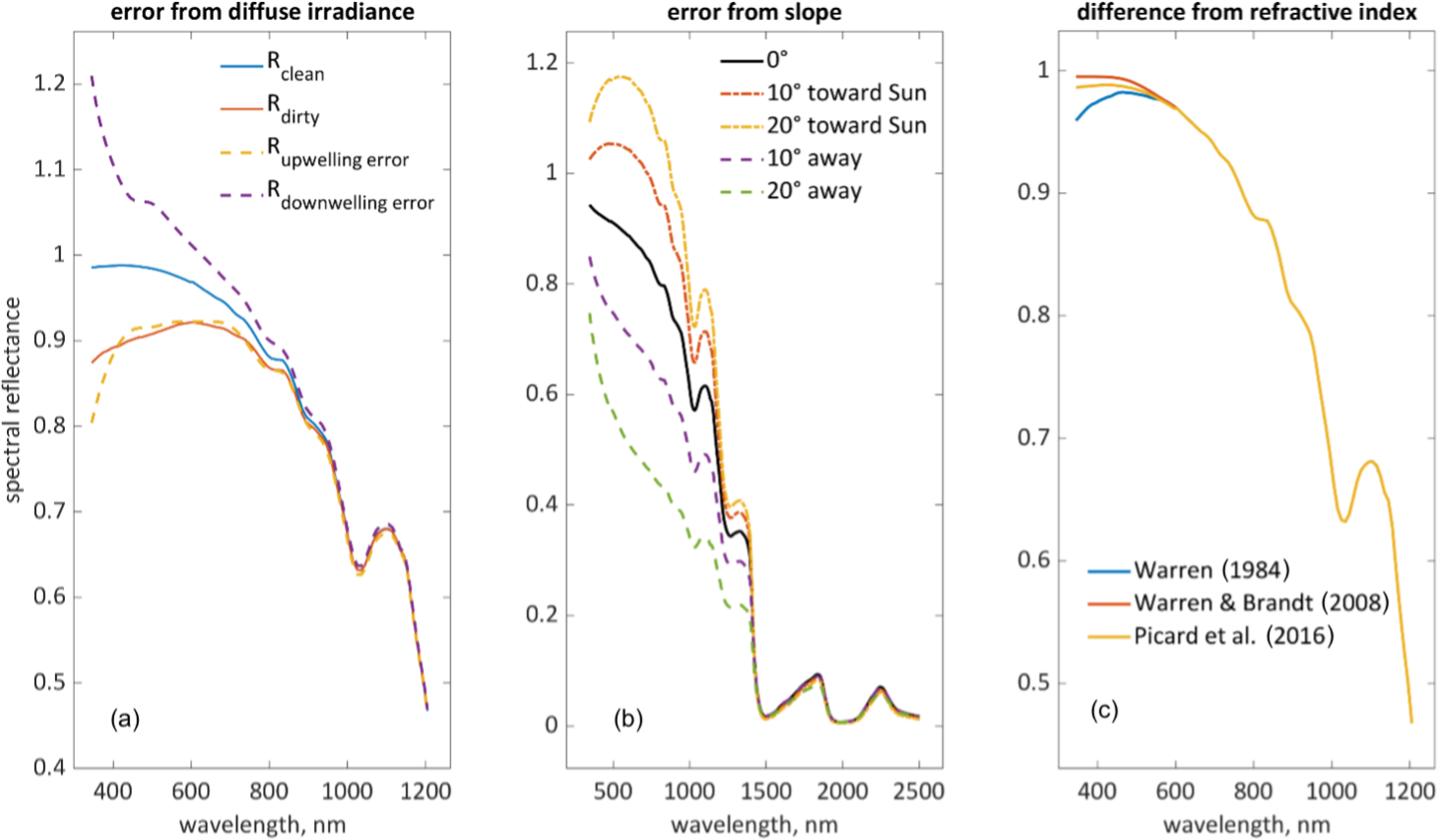

Due to properties of snow and refractive index of ice, clean snow reflects nearly all light near the visible end of the EM spectrum (350-600 nm). Although the refractive index of ice has a small source of unknown uncertainty (Picard et al., 2016), the relative uncertainty is much smaller than the errors that manifest from incorrect attribution of diffuse light in remote sensing methods.

When solving for snow reflectance quantity, some assumptions must be made in the forward model that represent surface, background, topography, and atmosphere to estimate the measured signal. However, more research is needed into the best ways of representing nature in the forward model such that the partitioning of direct to diffuse radiance is adequately accounted for. Any disparities will manifest into what Jeff Dozier dubbed as “the problematic hook” (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Differences in snow reflectance with respect background assumptions (left), topography (middle), refractive index of ice (right), as discussed in Bair et al. (2025).

“Shape from Spectra” principles in remote sensing of snow properties

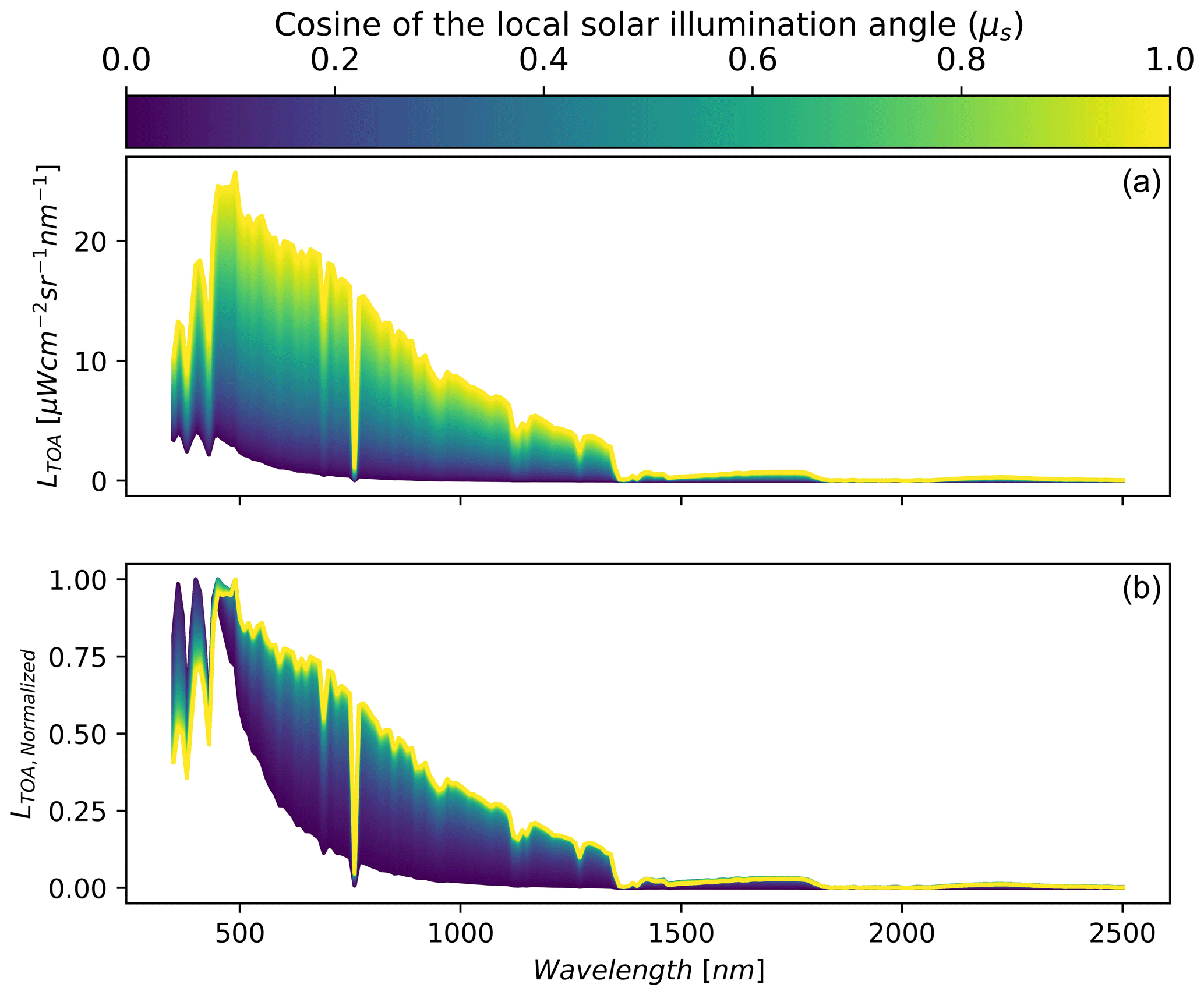

The local solar incidence angle can be inverted quite well from at-sensor imaging spectroscopy radiance due to the magnitude shift, but also the shape effect due to the diffuse fraction coming into play (Figure 2). This can be visualized by looking at the normalized radiance as shown below. This separability in this response space makes solving for this a well-posed problem for most models, and solves many issues related to poor representation of terrain (Figure 1). More research is needed however on how models designed like this may compensate for within-pixel surface roughness patterns and how this is represented physically.

Figure 2: Shape from spectra idea (Carmon et al., 2023) for synthetic snow example applied in in Wilder et al. (2024).

Figure 2: Shape from spectra idea (Carmon et al., 2023) for synthetic snow example applied in in Wilder et al. (2024).

Full-waveform lidar for retrieving snow optical grain sizes

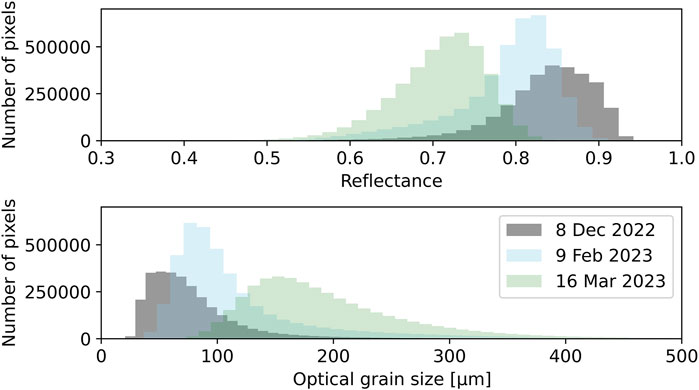

A highly understudied, but potentially interesting application of airborne lidar is leveraging the fact that common airborne sensors emit at 1064 nm and resolves complex terrain. This wavelength is significant because reflectance at 1064 nm is highly modulated by optical grain size, as it’s in proximity to high absorption band for ice at 1030 nm. However, there are currently some strong limitations that need to be researched further. Lidar intensity calibration, liquid water content of the snow, low lying clouds, atmospheric transmittance, atmospheric water vapor levels, and computational burden present stiff challenges at present. Future research may find success though using in situ calibration with across wide range of targets, multi-wavelength lidar technology, and access to continuous measurements of the atmosphere (e.g., AERONET)

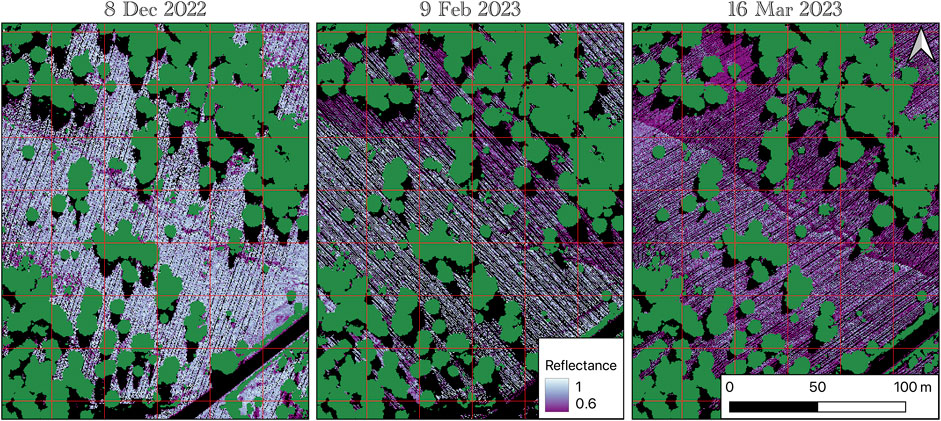

Figure 3: Derived snow reflectances and grain radii at 1064 nm from helicopter airborne lidar, published in Wilder et al. (2025).